Extended Mind: A teacher's guide

What is the extended mind and why is it important for teachers to consider?

Main, P (2021, June 07). Extended Mind: A teacher's guide. Retrieved from https://www.structural-learning.com/post/what-is-the-extended-mind

What is the extended mind and why is it important for teachers to consider?

Main, P (2021, June 07). Extended Mind: A teacher's guide. Retrieved from https://www.structural-learning.com/post/what-is-the-extended-mind

Andy Clark's extended mind thesis, originally published by Oxford University Press, in many ways was a hallmark paper. If you haven't watched one of his youtube interviews I thoroughly recommend you do so. His everyday examples of extended cognition capture the very essence of his philosophy. You'll hear many examples of how external resources are used to scaffold internal processes of the mind.

The extended cognition theory (Clark and Chalmers) states that we think not only with our brains, but with our bodies, the tools and technologies we use and the spaces in which we learn and work. Cognition is essentially shaped by action and experience. Our brain-centric culture, where intelligence is believed to be innate, individual, and internal, makes this theory particularly relevant for children. Children don't always conjure up new thoughts, action plays a central role in developing our cognitive processes.

Extended cognition is something we all embrace. Whether it be using our fingers to count with or writing down our ideas onto paper, we are extending the bounds of cognition by using an external resource. Cognitive processes are complicated and human intelligence has become increasingly entangled in technology. This cognitive integration is at the very centre of the extended mind hypothesis. Where exactly does the mind finish?

We cannot command the brain at will to learn, to pay attention, or to remember. It is instead a very specific and limited organ, one that evolved to perform tasks very distinct from those we ask of it today. It is not a matter of individual differences in intelligence, but of the limits of everyone's brain.

The biological brain excels at a number of things: sensing and moving the body, manipulating material objects, navigating through space, and interacting with others. By leveraging these natural strengths we will be able to facilitate and improve learning.

The brain isn't naturally adept at grasping abstract or counterintuitive ideas, ignoring distracting stimuli, or remembering information accurately and without error for a long period of time. As part of these functions, the brain needs "outside the brain" help, like the body, physical space, and tools, like social interactions.

When you're learning or studying, you don't want to sit in one spot, not moving, not talking, just pushing your brain to work harder. Distress and disappointment result from such an approach.

Gesturing is an integral part of a cognitive loop in which our hand motions influence our thoughts, and vice versa. The more gestures we make, the more fluent our thinking and speaking will be; the greater nuance and sophistication of our understanding. Have you ever watched someone give directions (without being able to hear them)? It's an impossible task to do without pointing or tracing your fingers. Here are some ways you can encourage the making of gestures:

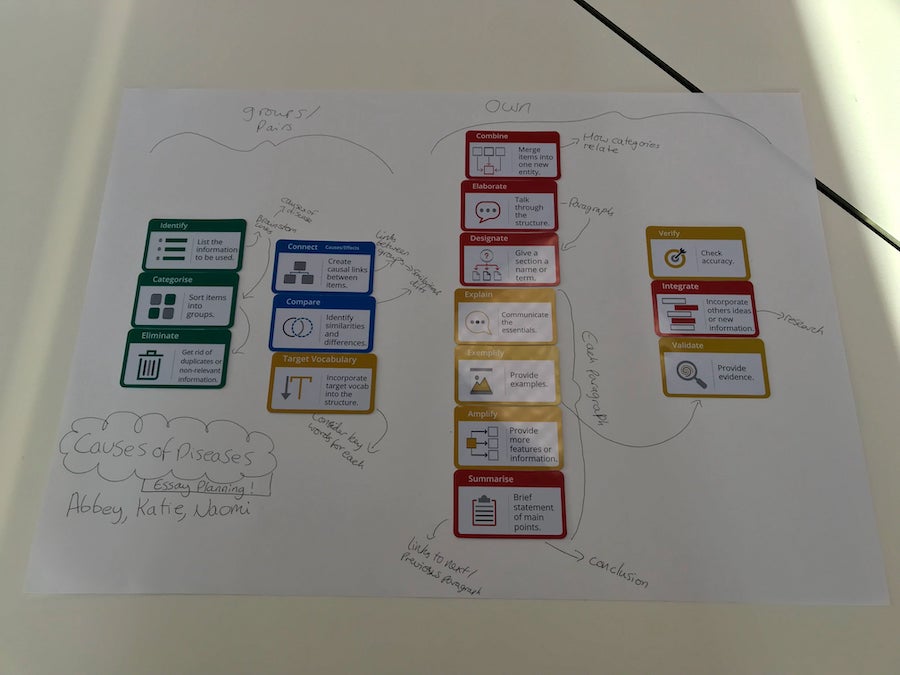

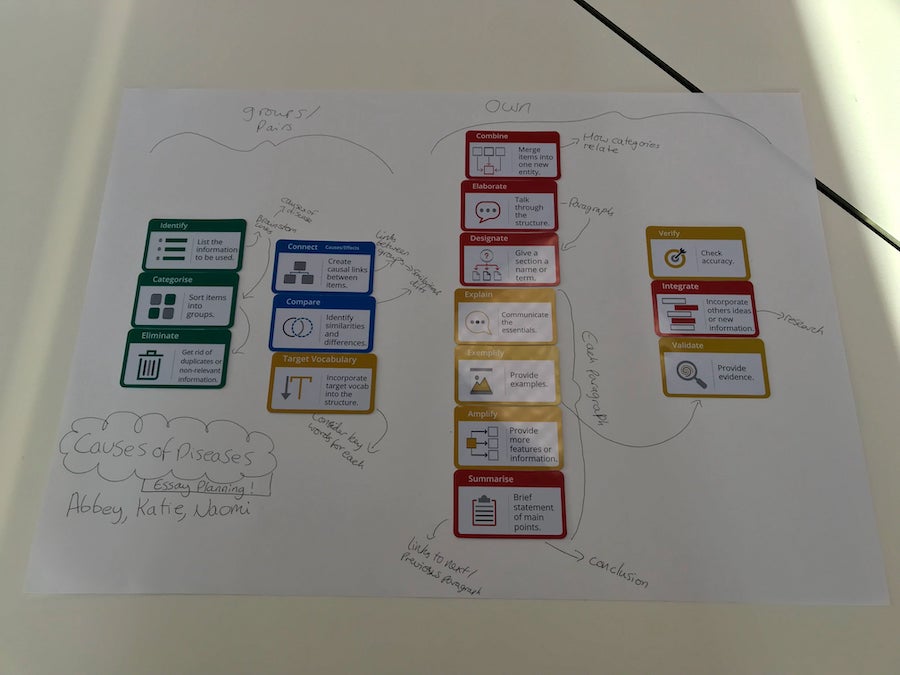

In school, we do way too much “in our heads”; we would all be thinking more efficiently and effectively if we offloaded our cognitive processes more often. A quick look at the cognitive load theory would suggest that 'freeing up' our cognitive resources plays an active role in enabling us to learn more effectively. This is a skill that can be cultivated—here are some ways I try to do so:

Experts who have difficulty teaching novices have "the curse of knowledge," which is when knowledge has become so automatic in their minds that they cannot explain it clearly to others. I am trying to keep in mind, as a teacher, that the curse of expertise applies to me. Chip and Dan Heath write about this topic in detail, once you are aware of the phenomenon, you'll immediately change your classroom practice.

1. What is the Extended Mind Theory?

The Extended Mind Theory, proposed by David Chalmers, suggests that human minds and mental processes are not confined within our brains but can extend into the environment. This cognitive extension implies that tools, objects, and even other people can become part of our minds. Research has explored this fascinating concept in depth.

2. How does the Extended Mind Hypothesis relate to social cognition?

The Extended Mind Hypothesis has significant implications for social cognition. It suggests that our understanding of others' minds can be influenced by our continuous interaction with them and our shared environment. This perspective can offer novel explanations of cognition in social contexts.

3. What does mental extension mean in the context of the Extended Mind Thesis?

Mental extension refers to the idea that our mental processes can extend beyond our brains into the external world. This could include using a notebook as an extension of our memory or a computer as an extension of our problem-solving abilities.

4. How does the Extended Mind Theory impact teaching and learning?

The Extended Mind Theory can transform our understanding of teaching and learning. It suggests that learning is not just an internal process but involves continuous interaction with others and the environment. This perspective can inform the development of teaching strategies that leverage these external resources.

5. What are the criticisms of the Extended Mind Theory?

While the Extended Mind Theory offers a unique perspective on cognition, it's not without criticism. Some argue that it overstates the role of external factors in cognition. Others question whether tools and objects can truly become part of our minds. Despite these debates, the Extended Mind Theory continues to stimulate thought-provoking discussions in cognitive science.

For a deeper dive into the Extended Mind Theory, you may refer to these research articles: Pressing the Flesh: A Tension in the Study of the Embodied, Embedded Mind?*, Extended emotion, From Wide Cognition to Mechanisms: A Silent Revolution, and The extended cognition thesis: Its significance for the philosophy of (cognitive) science.

Adams, F., and Aizawa, K. (2001). The bounds of cognition. Philos. Psychol. 14, 43–64. doi: 10.1080/09515080120033571 CrossRef Full Text Adams, F., and Aizawa, K. (2008). The Bounds of Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. (dx.doi.org)

Colombetti, G., Roberts, T. Extending the extended mind: the case for extended affectivity. Philos Stud 172, 1243–1263 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-014-0347-3 Download citation Published:

Andy Clark's extended mind thesis, originally published by Oxford University Press, in many ways was a hallmark paper. If you haven't watched one of his youtube interviews I thoroughly recommend you do so. His everyday examples of extended cognition capture the very essence of his philosophy. You'll hear many examples of how external resources are used to scaffold internal processes of the mind.

The extended cognition theory (Clark and Chalmers) states that we think not only with our brains, but with our bodies, the tools and technologies we use and the spaces in which we learn and work. Cognition is essentially shaped by action and experience. Our brain-centric culture, where intelligence is believed to be innate, individual, and internal, makes this theory particularly relevant for children. Children don't always conjure up new thoughts, action plays a central role in developing our cognitive processes.

Extended cognition is something we all embrace. Whether it be using our fingers to count with or writing down our ideas onto paper, we are extending the bounds of cognition by using an external resource. Cognitive processes are complicated and human intelligence has become increasingly entangled in technology. This cognitive integration is at the very centre of the extended mind hypothesis. Where exactly does the mind finish?

We cannot command the brain at will to learn, to pay attention, or to remember. It is instead a very specific and limited organ, one that evolved to perform tasks very distinct from those we ask of it today. It is not a matter of individual differences in intelligence, but of the limits of everyone's brain.

The biological brain excels at a number of things: sensing and moving the body, manipulating material objects, navigating through space, and interacting with others. By leveraging these natural strengths we will be able to facilitate and improve learning.

The brain isn't naturally adept at grasping abstract or counterintuitive ideas, ignoring distracting stimuli, or remembering information accurately and without error for a long period of time. As part of these functions, the brain needs "outside the brain" help, like the body, physical space, and tools, like social interactions.

When you're learning or studying, you don't want to sit in one spot, not moving, not talking, just pushing your brain to work harder. Distress and disappointment result from such an approach.

Gesturing is an integral part of a cognitive loop in which our hand motions influence our thoughts, and vice versa. The more gestures we make, the more fluent our thinking and speaking will be; the greater nuance and sophistication of our understanding. Have you ever watched someone give directions (without being able to hear them)? It's an impossible task to do without pointing or tracing your fingers. Here are some ways you can encourage the making of gestures:

In school, we do way too much “in our heads”; we would all be thinking more efficiently and effectively if we offloaded our cognitive processes more often. A quick look at the cognitive load theory would suggest that 'freeing up' our cognitive resources plays an active role in enabling us to learn more effectively. This is a skill that can be cultivated—here are some ways I try to do so:

Experts who have difficulty teaching novices have "the curse of knowledge," which is when knowledge has become so automatic in their minds that they cannot explain it clearly to others. I am trying to keep in mind, as a teacher, that the curse of expertise applies to me. Chip and Dan Heath write about this topic in detail, once you are aware of the phenomenon, you'll immediately change your classroom practice.

1. What is the Extended Mind Theory?

The Extended Mind Theory, proposed by David Chalmers, suggests that human minds and mental processes are not confined within our brains but can extend into the environment. This cognitive extension implies that tools, objects, and even other people can become part of our minds. Research has explored this fascinating concept in depth.

2. How does the Extended Mind Hypothesis relate to social cognition?

The Extended Mind Hypothesis has significant implications for social cognition. It suggests that our understanding of others' minds can be influenced by our continuous interaction with them and our shared environment. This perspective can offer novel explanations of cognition in social contexts.

3. What does mental extension mean in the context of the Extended Mind Thesis?

Mental extension refers to the idea that our mental processes can extend beyond our brains into the external world. This could include using a notebook as an extension of our memory or a computer as an extension of our problem-solving abilities.

4. How does the Extended Mind Theory impact teaching and learning?

The Extended Mind Theory can transform our understanding of teaching and learning. It suggests that learning is not just an internal process but involves continuous interaction with others and the environment. This perspective can inform the development of teaching strategies that leverage these external resources.

5. What are the criticisms of the Extended Mind Theory?

While the Extended Mind Theory offers a unique perspective on cognition, it's not without criticism. Some argue that it overstates the role of external factors in cognition. Others question whether tools and objects can truly become part of our minds. Despite these debates, the Extended Mind Theory continues to stimulate thought-provoking discussions in cognitive science.

For a deeper dive into the Extended Mind Theory, you may refer to these research articles: Pressing the Flesh: A Tension in the Study of the Embodied, Embedded Mind?*, Extended emotion, From Wide Cognition to Mechanisms: A Silent Revolution, and The extended cognition thesis: Its significance for the philosophy of (cognitive) science.

Adams, F., and Aizawa, K. (2001). The bounds of cognition. Philos. Psychol. 14, 43–64. doi: 10.1080/09515080120033571 CrossRef Full Text Adams, F., and Aizawa, K. (2008). The Bounds of Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. (dx.doi.org)

Colombetti, G., Roberts, T. Extending the extended mind: the case for extended affectivity. Philos Stud 172, 1243–1263 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-014-0347-3 Download citation Published: